First Epistle of Peter

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

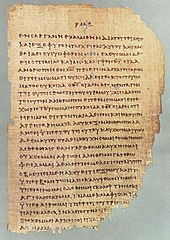

The First Epistle of Peter, usually referred to simply as First Peter and often written 1 Peter, is a book of the New Testament. The author presents himself as Peter the Apostle, and the epistle was traditionally held to have been written during his time as bishop of Rome or Bishop of Antioch, though neither title is used in the epistle. The letter is addressed to various churches in Asia Minor suffering religious persecution.Books of the

New Testament

Gospels Acts Acts of the Apostles Epistles Romans

1 Corinthians · 2 Corinthians

Galatians · Ephesians

Philippians · Colossians

1 Thessalonians · 2 Thessalonians

1 Timothy · 2 Timothy

Titus · Philemon

Hebrews · James

1 Peter · 2 Peter

1 John · 2 John · 3 John

JudeApocalypse Revelation New Testament manuscripts

Contents

Authorship

Main article: Authorship of the Petrine epistlesThe authorship of 1 Peter has traditionally been attributed to the Apostle Peter because it bears his name and identifies him as its author (1:1). Although the text identifies Peter as its author the language, dating, style, and structure of this letter has led many scholars to conclude that this letter is pseudonymous. Many scholars are convinced that Peter was not the author of this letter because the author had to have a formal education in rhetoric/philosophy and an advanced knowledge of the Greek language.[1]

Graham Stanton rejects Petrine authorship because 1 Peter was most likely written during the reign of Domitian in AD 81, which is when he believes widespread Christian persecution began, which is long after the death of Peter.[2] Current scholarship has abandoned the persecution argument because the described persecution within the work does not necessitate a time period outside of the period of Peter.[3] Many scholars also doubt Petrine authorship because they are convinced that 1 Peter is dependent on the Pauline epistles and thus was written after Paul the Apostle’s ministry because it shares many of the same motifs espoused in Ephesians, Colossians, and the Pastoral Epistles.[4] Others argue that it makes little sense to ascribe the work to Peter when it could have been ascribed to Paul.[3] One theory used to support Petrine authorship of 1 Peter is the "secretarial hypothesis", which suggests that 1 Peter was dictated by Peter and was written in Greek by his secretary, Silvanus (5:12). John Elliot, however, suggests that the notion of Silvanus as secretary or author or drafter of 1 Peter represents little more than a counsel of despair and introduces more problems than it solves because the Greek rendition of 5:12 suggests that Silvanus was not the secretary, but the courier/bearer of 1 Peter,[5] and some see Mark as a contributive amanuensis in the composition and writing of the work.[6][7] On the one hand, some scholars such as Bart D. Ehrman[8] are convinced that the language, dating, literary style, and structure of this text makes it implausible to conclude that 1 Peter was written by Peter; according to these scholars, it is more likely that 1 Peter is a pseudonymous letter, written later by one of the disciples of Peter in his honor. On the other hand, some scholars argue that there is not enough evidence to conclude that Peter did not write 1 Peter. For instance, there are similarities between 1 Peter and Peter's speeches in the Biblical book of Acts,[9] and the earliest attestation of Peter's authorship comes from 2 Peter (AD 60–160)[10] and the letters of Clement (AD 70-140).[3] Ultimately, the authorship of 1 Peter remains contested.

Audience

1 Peter is addressed to the “elect resident aliens” scattered throughout Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia. The five areas listed in 1:1 as the geographical location of the first readers were Roman provinces in Asia Minor. The order in which the provinces are listed may reflect the route to be taken by the messenger who delivered the circular letter. The recipients of this letter are referred to in 1:1 as “exiles of the Dispersion.” In 1:17, they are urged to “live in reverent fear during the time of your exile".[11] The social makeup of the addressees of 1 Peter is debatable because some scholars interpret “strangers” (1:1) as Christians longing for their home in heaven, some interpret it as literal “strangers”, or as an Old Testament adaptation applied to Christian believers.[11]

While the new Christians have encountered oppression and hostility from locals, Peter advises them to maintain loyalty to both their religion and the Roman Empire (1 Peter 2:17).[12]

The author counsels (1) to steadfastness and perseverance under persecution (1–2:10); (2) to the practical duties of a holy life (2:11–3:13); (3) he adduces the example of Christ and other motives to patience and holiness (3:14–4:19); and (4) concludes with counsels to pastors and people (chap. 5).

Outline

David Bartlett lists the following outline to structure the literary divisions of 1 Peter.[4]

- Greeting (1:1–2)

- Praise to God (1:3–12)

- God's Holy People (1:13–2:10)

- Life in Exile (2:11–4:11)

- Steadfast in Faith (4:12–5:11)

- Final Greeting (5:12–14)

Part of a series on Saint Peter

In the New Testament Other Context

The Petrine author writes of his addressees undergoing “various trials” (1 Peter 1:6), being “tested by fire” (1:7), maligned “as evildoers” (2:12) and suffering “for doing good” (3:17). Based on such internal evidence, biblical scholar John Elliott summarizes the addressees’ situation as one marked by undeserved suffering.[13] Verse (3:19), "Spirits in prison", is a continuing theme in Christianity, and one considered by most theologians to be enigmatic and difficult to interpret.[14]

A number of verses in the epistle contain possible clues about the reasons Christians experienced opposition. Exhortations to live blameless lives (2:15; 3:9, 13, 16) may suggest that the Christian addressees were accused of immoral behavior, and exhortations to civil obedience (2:13–17) perhaps imply that they were accused of disloyalty to governing powers.[1]

However, scholars differ on the nature of persecution inflicted on the addressees of 1 Peter. Some read the epistle to be describing persecution in the form of social discrimination, while some read them to be official persecution.[citation needed]

Social discrimination of Christians

Some scholars believe that the sufferings the epistle's addressees were experiencing were social in nature, specifically in the form of verbal derision.[15] Internal evidence for this includes the use of words like “malign” (2:12; 3:16), and “reviled” (4:14). Biblical scholar John Elliott notes that the author explicitly urges the addressees to respect authority (2:13) and even honor the emperor (2:17), strongly suggesting that they were unlikely to be suffering from official Roman persecution. It is significant to him that the author notes that “your brothers and sisters in all the world are undergoing the same kinds of suffering” (5:9), indicating suffering that is worldwide in scope. Elliott sees this as grounds to reject the idea that the epistle refers to official persecution, because the first worldwide persecution of Christians officially meted by Rome did not occur until the persecution initiated by Decius in AD 250.

Official persecution of Christians

On the other hand, scholars who support the official persecution theory take the exhortation to defend one's faith (3:15) as a reference to official court proceedings.[1] They believe that these persecutions involved court trials before Roman authorities, and even executions.[citation needed]

One common supposition is that 1 Peter was written during the reign of Domitian (AD 81–96). Domitian's aggressive claim to divinity would have been rejected and resisted by Christians. Biblical scholar Paul Achtemeier believes that persecution of Christians by Domitian would have been in character, but points out that there is no evidence of official policy targeted specifically at Christians. If Christians were persecuted, it is likely to have been part of Domitian’s larger policy suppressing all opposition to his self-proclaimed divinity.[1] There are other scholars who explicitly dispute the idea of contextualizing 1 Peter within Domitian’s reign. Duane Warden believes that Domitian’s unpopularity even among Romans renders it highly unlikely that his actions would have great influence in the provinces, especially those under the direct supervision of the senate such as Asia (one of the provinces 1 Peter is addressed to).[16]

Also often advanced as a possible context for 1 Peter is the trials and executions of Christians in the Roman province of Bithynia-Pontus under Pliny the Younger. Scholars who support this theory believe that a famous letter from Pliny to Emperor Trajan concerning the delation of Christians reflects the situation faced by the addressees of this epistle.[17][18] In Pliny's letter, written in AD 112, he asks Trajan if the accused Christians brought before him should be punished based on the name ‘Christian’ alone, or for crimes associated with the name. For biblical scholar John Knox, the use of the word “name” in 4:14–16 is the “crucial point of contact” with that in Pliny’s letter.[17] In addition, many scholars in support of this theory believe that there is content within 1 Peter that directly mirrors the situation as portrayed in Pliny’s letter. For instance, they interpret the exhortation to defend one’s faith “with gentleness and reverence” in 3:15–16 as a response to Pliny executing Christians for the obstinate manner in which they professed to be Christians. Generally, this theory is rejected mainly by scholars who read the suffering in 1 Peter to be caused by social, rather than official, discrimination.[citation needed]

The Harrowing of Hell

Main article: Harrowing of HellThe author refers to Jesus, after his death, proclaiming to spirits in prison (3:18–20). This passage, and a few others (such as Matthew 27:52 and Luke 23:43), are the basis of the traditional Christian belief in the descent of Christ into hell, or the harrowing of hell.[19] Though interpretations vary, some theologians[who?] see this passage as referring to Jesus, after his death, going to a place (neither heaven nor hell in the ultimate sense) where the souls of pre-Christian people waited for the Gospel. The first creeds to mention the harrowing of hell were Arian formularies of Sirmium (359), Nike (360), and Constantinople (360). It spread through the west and later appeared in the Apostles' Creed".[19]

See also

Notes

- Achtemeier, Paul. Peter 1 Hermeneia. Fortress Press. 1996

- Stanton, Graham. Eerdmans Commentary of the Bible. Wm.B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2003.

- Travis B. Williams (1 November 2012). Persecution in 1 Peter: Differentiating and Contextualizing Early Christian Suffering. BRILL. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-90-04-24189-3. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Bartlett, David. New Interpreters Bible Commentary, 1 Peter. Abingdon Press. 1998.

- Elliot, John. 1 Peter: Anchor Bible Commentary. Yale University Press. 2001.

- Travis B. Williams (1 November 2012). Persecution in 1 Peter: Differentiating and Contextualizing Early Christian Suffering. BRILL. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-90-04-24189-3. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Jongyoon Moon (30 November 2009). Mark As Contributive Amanuensis of 1 Peter?. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-10428-1. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2011). Forged. HarperOne, HarperCollins. pp. 65–77. ISBN 978-0-06-201262-3.

- Daniel Keating, First and Second Peter Jude (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2011) 18. Norman Hillyer, 1 and 2 Peter, Jude, New International Biblical Commentary (Peabody, MA: Henrickson, 1992), 1–3. Karen H. Jobes, 1 Peter(Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005), 14–19).

- Bauckham, RJ (1983), Word Bible Commentary, Vol.50, Jude-2 Peter, Waco

- Stanton, Graham. Eerdmans Commentary of the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2003.

- "Peter, first letter of" A Dictionary of the Bible. by W. R. F. Browning. Oxford University Press Inc. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. University of Chicago. 10 May 2012 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t94.e1457>

- Elliott, John. 1 Peter: a new translation with introduction and commentary. Yale University Press. 2000

- Christian Monthly Standard http://www.christianmonthlystandard.com/index.php/preached-to-the-spirits-in-prison-1-peter-318-20/

- Elliott, John. I Peter: a new translation with introduction and commentary. Yale University Press. 2000

- Warden, Duane. Imperial Persecution and the Dating of 1 Peter and Revelation. Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 34:2. 1991

- Knox, John. Pliny and I Peter: A Note on I Peter 4:14–16 and 3:15. Journal of Biblical Literature 72:3. 1953

- Downing, F Gerald. Pliny's Prosecutions of Christians: Revelation and 1 Peter. Journal for the Study of the New Testament 34. 1988

"Descent of Christ into Hell." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

New!Clean Pure Christlike energy to move 1063 pounds of bricks in one sheer movement using the power of a man's back or horses requires energy.That is all!Abraham had no four wheel engined vehicle but he had faith and common sense to do whatever God demanded of him in a way that was efficient and respectful to all of God's creation of which he was a part.Abraham also had no written law; also true for Joseph or Jacob or Moses when Moses crossed the red sea.All posts are authored by Warren A.Lyon.

Search This Blog

Wednesday, 25 January 2017

1st Peter, Christian persecution and the harrowing of Hell!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Epistle_of_Peter

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment