With passions so little active, and so good a curb, men, being rather

wild than wicked, and more intent to guard themselves against the

mischief that might be done them, than to do mischief to others, were by

no means subject to very perilous dissensions. They maintained no kind

of intercourse with one another, and were consequently strangers to

vanity, deference, esteem and contempt; they had not the least idea of

meum and tuum, and no true conception of justice; they looked upon every

violence to which they were subjected, rather as an injury that might

easily be repaired than as a crime that ought to be punished; and they

never thought of taking revenge, unless perhaps mechanically and on the

spot, as a dog will sometimes bite the stone which is thrown at him.

Their quarrels therefore would seldom have very bloody consequences; for

the subject of them would be merely the question of subsistence. But I

am aware of one greater danger, which remains to be noticed.

Of the passions that stir the heart of man, there is one which makes the

sexes necessary to each other, and is extremely ardent and impetuous; a

terrible passion that braves danger, surmounts all obstacles, and in its

transports seems calculated to bring destruction on the human race which

it is really destined to preserve. What must become of men who are left

to this brutal and boundless rage, without modesty, without shame, and

daily upholding their amours at the price of their blood?

It must, in the first place, be allowed that, the more violent the

passions are, the more are laws necessary to keep them under restraint.

But, setting aside the inadequacy of laws to effect this purpose, which

is evident from the crimes and disorders to which these passions daily

give rise among us, we should do well to inquire if these evils did not

spring up with the laws themselves; for in this case, even if the laws

were capable of repressing such evils, it is the least that could be

expected from them, that they should check a mischief which would not

have arisen without them.

Let us begin by distinguishing between the physical and moral

ingredients in the feeling of love. The physical part of love is that

general desire which urges the sexes to union with each other. The moral

part is that which determines and fixes this desire exclusively upon one

particular object; or at least gives it a greater degree of energy

toward the object thus preferred. It is easy to see that the moral part

of love is a factitious feeling, born of social usage, and enhanced by

the women with much care and cleverness, to establish their empire, and

put in power the sex which ought to obey. This feeling, being founded on

certain ideas of beauty and merit which a savage is not in a position to

acquire, and on comparisons which he is incapable of making, must be for

him almost non-existent; for, as his mind cannot form abstract ideas of

proportion and regularity, so his heart is not susceptible of the

feelings of love and admiration, which are even insensibly produced by

the application of these ideas. He follows solely the character nature

has implanted in him, and not tastes which he could never have acquired;

so that every woman equally answers his purpose.

Men in a state of nature being confined merely to what is physical in

love, and fortunate enough to be ignorant of those excellences, which

whet the appetite while they increase the difficulty of gratifying it,

must be subject to fewer and less violent fits of passion, and

consequently fall into fewer and less violent disputes. The imagination,

which causes such ravages among us, never speaks to the heart of

savages, who quietly await the impulses of nature, yield to them

involuntarily, with more pleasure than ardour, and, their wants once

satisfied, lose the desire. It is therefore incontestable that love, as

well as all other passions, must have acquired in society that glowing

impetuosity, which makes it so often fatal to mankind. And it is the

more absurd to represent savages as continually cutting one another's

throats to indulge their brutality, because this opinion is directly

contrary to experience; the Caribbeans, who have as yet least of all

deviated from the state of nature, being in fact the most peaceable of

people in their amours, and the least subject to jealousy, though they

live in a hot climate which seems always to inflame the passions.

With regard to the inferences that might be drawn, in the case of

several species of animals, the males of which fill our poultry-yards

with blood and slaughter, or in spring make the forests resound with

their quarrels over their females; we must begin by excluding all those

species, in which nature has plainly established, in the comparative

power of the sexes, relations different from those which exist among us:

thus we can base no conclusion about men on the habits of fighting

cocks. In those species where the proportion is better observed, these

battles must be entirely due to the scarcity of females in comparison

with males; or, what amounts to the same thing, to the intervals during

which the female constantly refuses the advances of the male: for if

each female admits the male but during two months in the year, it is the

same as if the number of females were five-sixths less. Now, neither of

these two cases is applicable to the human species, in which the number

of females usually exceeds that of males, and among whom it has never

been observed, even among savages, that the females have, like those of

other animals, their stated times of passion and indifference. Moreover,

in several of these species, the individuals all take fire at once, and

there comes a fearful moment of universal passion, tumult and disorder

among them; a scene which is never beheld in the human species, whose

love is not thus seasonal. We must not then conclude from the combats of

such animals for the enjoyment of the females, that the case would be

the same with mankind in a state of nature: and, even if we drew such a

conclusion, we see that such contests do not exterminate other kinds of

animals, and we have no reason to think they would be more fatal to

ours. It is indeed clear that they would do still less mischief than is

the case in a state of society; especially in those countries in which,

morals being still held in some repute, the jealousy of lovers and the

vengeance of husbands are the daily cause of duels, murders, and even

worse crimes; where the obligation of eternal fidelity only occasions

adultery, and the very laws of honour and continence necessarily

increase debauchery and lead to the multiplication of abortions.

Let us conclude then that man in a state of nature, wandering up and

down the forests, without industry, without speech, and without home, an

equal stranger to war and to all ties, neither standing in need of his

fellow-creatures nor having any desire to hurt them, and perhaps even

not distinguishing them one from another; let us conclude that, being

self-sufficient and subject to so few passions, he could have no

feelings or knowledge but such as befitted his situation; that he felt

only his actual necessities, and disregarded everything he did not think

himself immediately concerned to notice, and that his understanding made

no greater progress than his vanity. If by accident he made any

discovery, he was the less able to communicate it to others, as he did

not know even his own children. Every art would necessarily perish with

its inventor, where there was no kind of education among men, and

generations succeeded generations without the least advance; when, all

setting out from the same point, centuries must have elapsed in the

barbarism of the first ages; when the race was already old, and man

remained a child.

If I have expatiated at such length on this supposed primitive state, it

is because I had so many ancient errors and inveterate prejudices to

eradicate, and therefore thought it incumbent on me to dig down to their

very root, and show, by means of a true picture of the state of nature,

how far even the natural inequalities of mankind are from having that

reality and influence which modern writers suppose.

It is in fact easy to see that many of the differences which distinguish

men are merely the effect of habit and the different methods of life men

adopt in society. Thus a robust or delicate constitution, and the

strength or weakness attaching to it, are more frequently the effects of

a hardy or effeminate method of education than of the original endowment

of the body. It is the same with the powers of the mind; for education

not only makes a difference between such as are cultured and such as are

not, but even increases the differences which exist among the former, in

proportion to their respective degrees of culture: as the distance

between a giant and a dwarf on the same road increases with every step

they take. If we compare the prodigious diversity, which obtains in the

education and manner of life of the various orders of men in the state

of society, with the uniformity and simplicity of animal and savage

life, in which every one lives on the same kind of food and in exactly

the same manner, and does exactly the same things, it is easy to

conceive how much less the difference between man and man must be in a

state of nature than in a state of society, and how greatly the natural

inequality of mankind must be increased by the inequalities of social

institutions.

But even if nature really affected, in the distribution of her gifts,

that partiality which is imputed to her, what advantage would the

greatest of her favourites derive from it, to the detriment of others,

in a state that admits of hardly any kind of relation between them?

Where there is no love, of what advantage is beauty? Of what use is wit

to those who do not converse, or cunning to those who have no business

with others? I hear it constantly repeated that, in such a state, the

strong would oppress the weak; but what is here meant by oppression?

Some, it is said, would violently domineer over others, who would groan

under a servile submission to their caprices. This indeed is exactly

what I observe to be the case among us; but I do not see how it can be

inferred of men in a state of nature, who could not easily be brought to

conceive what we mean by dominion and servitude. One man, it is true,

might seize the fruits which another had gathered, the game he had

killed, or the cave he had chosen for shelter; but how would he ever be

able to exact obedience, and what ties of dependence could there be

among men without possessions? If, for instance, I am driven from one

tree, I can go to the next; if I am disturbed in one place, what hinders

me from going to another? Again, should I happen to meet with a man so

much stronger than myself, and at the same time so depraved, so

indolent, and so barbarous, as to compel me to provide for his

sustenance while he himself remains idle; he must take care not to have

his eyes off me for a single moment; he must bind me fast before he goes

to sleep, or I shall certainly either knock him on the head or make my

escape. That is to say, he must in such a case voluntarily expose

himself to much greater trouble than he seeks to avoid, or can give me.

After all this, let him be off his guard ever so little; let him but

turn his head aside at any sudden noise, and I shall be instantly twenty

paces off, lost in the forest, and, my fetters burst asunder, he would

never see me again.

Without my expatiating thus uselessly on these details, every one must

see that as the bonds of servitude are formed merely by the mutual

dependence of men on one another and the reciprocal needs that unite

them, it is impossible to make any man a slave, unless he be first

reduced to a situation in which he cannot do without the help of others:

and, since such a situation does not exist in a state of nature, every

one is there his own master, and the law of the strongest is of no

effect.

Having proved that the inequality of mankind is hardly felt, and that

its influence is next to nothing in a state of nature, I must next show

its origin and trace its progress in the successive developments of the

human mind. Having shown that human perfectibility, the social virtues,

and the other faculties which natural man potentially possessed, could

never develop of themselves, but must require the fortuitous concurrence

of many foreign causes that might never arise, and without which he

would have remained for ever in his primitive condition, I must now

collect and consider the different accidents which may have improved the

human understanding while depraving the species, and made man wicked

while making him sociable; so as to bring him and the world from that

distant period to the point at which we now behold them.

I confess that, as the events I am going to describe might have happened

in various ways, I have nothing to determine my choice but conjectures:

but such conjectures become reasons, when they are the most probable

that can be drawn from the nature of things, and the only means of

discovering the truth. The consequences, however, which I mean to deduce

will not be barely conjectural; as, on the principles just laid down, it

would be impossible to form any other theory that would not furnish the

same results, and from which I could not draw the same conclusions.

This will be a sufficient apology for my not dwelling on the manner in

which the lapse of time compensates for the little probability in the

events; on the surprising power of trivial causes, when their action is

constant; on the impossibility, on the one hand, of destroying certain

hypotheses, though on the other we cannot give them the certainty of

known matters of fact; on its being within the province of history, when

two facts are given as real, and have to be connected by a series of

intermediate facts, which are unknown or supposed to be so, to supply

such facts as may connect them; and on its being in the province of

philosophy when history is silent, to determine similar facts to serve

the same end; and lastly, on the influence of similarity, which, in the

case of events, reduces the facts to a much smaller number of different

classes than is commonly imagined. It is enough for me to offer these

hints to the consideration of my judges, and to have so arranged that

the general reader has no need to consider them at all.

THE SECOND PART

THE first man who, having enclosed a piece of ground, bethought himself

of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe him,

was the real founder of civil society. From how many crimes, wars and

murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have

saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and

crying to his fellows, "Beware of listening to this impostor; you are

undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all,

and the earth itself to nobody." But there is great probability that

things had then already come to such a pitch, that they could no longer

continue as they were; for the idea of property depends on many prior

ideas, which could only be acquired successively, and cannot have been

formed all at once in the human mind. Mankind must have made very

considerable progress, and acquired considerable knowledge and industry

which they must also have transmitted and increased from age to age,

before they arrived at this last point of the state of nature. Let us

then go farther back, and endeavour to unify under a single point of

view that slow succession of events and discoveries in the most natural

order.

Man's first feeling was that of his own existence, and his first care

that of self-preservation. The produce of the earth furnished him with

all he needed, and instinct told him how to use it. Hunger and other

appetites made him at various times experience various modes of

existence; and among these was one which urged him to propagate his

species -- a blind propensity that, having nothing to do with the heart,

produced a merely animal act. The want once gratified, the two sexes

knew each other no more; and even the offspring was nothing to its

mother, as soon as it could do without her.

Such was the condition of infant man; the life of an animal limited at

first to mere sensations, and hardly profiting by the gifts nature

bestowed on him, much less capable of entertaining a thought of forcing

anything from her. But difficulties soon presented themselves, and it

became necessary to learn how to surmount them: the height of the trees,

which prevented him from gathering their fruits, the competition of

other animals desirous of the same fruits, and the ferocity of those who

needed them for their own preservation, all obliged him to apply himself

to bodily exercises. He had to be active, swift of foot, and vigorous in

fight. Natural weapons, stones and sticks, were easily found: he learnt

to surmount the obstacles of nature, to contend in case of necessity

with other animals, and to dispute for the means of subsistence even

with other men, or to indemnify himself for what he was forced to give

up to a stronger.

In proportion as the human race grew more numerous, men's cares

increased. The difference of soils, climates and seasons, must have

introduced some differences into their manner of living. Barren years,

long and sharp winters, scorching summers which parched the fruits of

the earth, must have demanded a new industry. On the seashore and the

banks of rivers, they invented the hook and line, and became fishermen

and eaters of fish. In the forests they made bows and arrows, and became

huntsmen and warriors. In cold countries they clothed themselves with

the skins of the beasts they had slain. The lightning, a volcano, or

some lucky chance acquainted them with fire, a new resource against the

rigours of winter: they next learned how to preserve this element, then

how to reproduce it, and finally how to prepare with it the flesh of

animals which before they had eaten raw.

New!Clean Pure Christlike energy to move 1063 pounds of bricks in one sheer movement using the power of a man's back or horses requires energy.That is all!Abraham had no four wheel engined vehicle but he had faith and common sense to do whatever God demanded of him in a way that was efficient and respectful to all of God's creation of which he was a part.Abraham also had no written law; also true for Joseph or Jacob or Moses when Moses crossed the red sea.All posts are authored by Warren A.Lyon.

Search This Blog

Sunday, 30 April 2017

So, we really cant tell a client what they are doing but if the machine transmitted something running on DOS with a fax modem on a reboot two contracts of the same amount, same currency and same rate in 24-48 hours, then it is likely to be a duplicate. But, what does the customer think?

So, we really can't tell a client what they are doing but if the machine transmitted something running on DOS with a fax modem on a reboot two contracts of the same amount, same currency and same rate in 24-48 hours, then it is likely to be a duplicate. But, what does the customer think? They have to agree and you go through it on the recorded line and they pull their fx Quenta dough folder and then they confirm at Nutella Credit Union or at Converse City Credit Union. In loss prevention, if the report is generated once a day of outstanding contracts, you will see the unprocessed duplicate one day after but the client does know its a duplicate but they might see that the machine transmitted the report twice but they also presume we have a way of knowing what is a duplicate since it is the biggest Mcdonalds Bank in the world; innit? But back office processing cannot say it is a duplicate. It is not their job. The rate goes down and the contract is processed twice but the trader is only paid for one rate booking; right Pauley? Once processed twice, the bank needs payment twice but the customer only sends payment once but their credit facility is booked twice. I propose here at Cyberdyne Genysis a filter for Bank of Mcdonalds that will pend a second contract that meets the variables of same amount, same currency and same rate in 24-48 hours. Right Pauley? There is one person who knows the contract is a duplicate. He works for Cyberdyne Genesys.

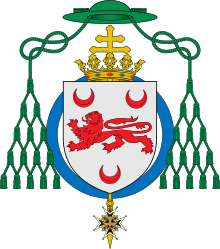

Bible study this week and the meaning of the tassels as read by Warren at the heralding of the Virgin and of the Christ.... Ecclesiastical heraldry:

Ecclesiastical heraldry

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Coat of arms of Cardinal Agostino Bausa in the courtyard of the archiepiscopal palace of Florence

Ecclesiastical heraldry refers to the use of heraldry within the Christian Church for dioceses and Christian clergy. Initially used to mark documents, ecclesiastical heraldry evolved as a system for identifying people and dioceses. It is most formalized within the Catholic Church, where most bishops, including the Pope, have a personal coat of arms. Clergy in Anglican, Lutheran, Eastern Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches follow similar customs, as do institutions such as schools and dioceses.

Ecclesiastical heraldry differs notably from other heraldry in the use of special insignia around the shield to indicate rank in a church or denomination. The most prominent of these insignia is the low crowned, wide brimmed ecclesiastical hat, commonly the Roman galero. The color and ornamentation of this hat indicate rank. Cardinals are famous for the "red hat", but other offices and other churches have distinctive hat colors, such as black for ordinary clergy and green for bishops, customarily with a number of tassels increasing with rank.

Other insignia include the processional cross, the mitre and the crosier. Eastern traditions favor the use of their own style of head gear and crosier, and the use of the mantle or cloak rather than the ecclesiastical hat. The motto and certain shapes of shields are more common in ecclesiastical heraldry, while supporters and crests are less common. The papal coats of arms have their own heraldic customs, primarily the Papal Tiara (or mitre), the keys of Saint Peter, and the ombrellino (umbrella). Pope Benedict XVI replaced the use of the Papal Tiara in his coat of arms with a mitre. He was the first pope to do so, despite the fact that Pope Paul VI was the last pope to be crowned with the tiara. The arms of institutions have slightly different traditions, using the mitre and crozier more often than is found in personal arms, though there is a wide variation in uses by different churches. The arms used by organizations are called impersonal or corporate arms.

Contents

1 History

2 Shield

2.1 Personal design

2.2 Marshalling

3 Around the shield

3.1 Ecclesiastical hat

3.2 Cross

3.3 Mitre and pallium

3.4 Crosier

3.5 Mantle

3.6 Motto

4 Papal insignia

5 Chivalric insignia

6 References

7 Bibliography

8 External links

History

12th-century seal of Stefan of Uppsala

Reproduction of a medieval Knights Templar Seal

personal seal of Martin Luther from 1530, now a symbol of Lutheranism

Heraldry developed in medieval Europe from the late 11th century, originally as a system of personal badges of the warrior classes, which served, among other purposes, as identification on the battlefield. The same insignia were used on seals to identify documents. The earliest seals bore a likeness of the owner of the seal, with the shield and heraldic insignia included.[1] Over time, the seals were reduced to just the shield.

The Church likewise identified the origin and ownership of documents and buildings with seals, which were typically a pointed oval called a vesica to distinguish from round seals in non-religious use.[2] Edward I of England decreed in 1307 that all legal documents required a seal.[3] These seals initially depicted a person, but as secular seals began to depict only a shield, clergy likewise used seals with heraldic insignia.[4] Personal seals of bishops and abbots continued to be used after their deaths, gradually becoming an impersonal seal.[3] Clergy tended to replace military devices with clerical devices. The shield was retained, but ecclesiastical hats often replaced helmets and coronets. In some religious arms a skull replaces the helmet.[5]

The structure of Church heraldry developed significantly in the 17th century when a system for ecclesiastical hats attributed to Pierre Palliot came into use.[6] The full system of emblems around the shield was regulated in the Catholic Church by the letter of Pope Pius X Inter multiplices curas of February 21, 1905, while the composition of the shield itself was regulated through the Heraldry Commission of the Roman Curia until this office was abolished by Pope John XXIII in 1960.[7] The Annuario Pontificio ceased publishing the arms of Cardinals and previous Popes after 1969. International custom and national law govern limited aspects of Church heraldry, but shield composition is now largely guided by expert advice. Archbishop Bruno Heim, a noted ecclesiastical armorist (designer of arms), said

Ecclesiastical heraldry is not determined by heraldic considerations alone, but also by doctrinal, liturgical and canonical factors. It not only produces arms denoting members of the ecclesiastical state but shows the rank of the bearer.... In the eyes of the Church it is sufficient to determine who has a right to bear an ecclesiastical coat of arms and under what conditions the different insignia are acquired or lost... The design of prelatial arms is often a disastrous defiance of the rules of heraldry, if only as a breach of good taste.[8]

A similar system for the Church of England was approved in 1976.[9] The traditions of Eastern Christian heraldry have less developed regulation. Eastern secular coats of arms often display a shield before a mantle topped with a crown. Eastern clergy often display coats of arms according to this style, replacing the crown with an appropriate hat drawn from liturgical use.

Marking documents is the most common use of arms in the Church today. A Roman Catholic bishop's coat of arms was formerly painted on miniature wine barrels and presented during the ordination ceremony.[10][11] Cardinals may place their coat of arms outside the church of their title in Rome.[12] Impersonal arms are often used as the banner of a school or religious community.

Shield

Arms of an abbess displayed on a lozenge with crosier turned left

The shield is the normal device for displaying a coat of arms. Clergy have used less-military shapes such as the oval cartouche, but the shield has always been a clerical option. Clergy in Italy often use a shield shaped like a horse's face-armor. Clergy in South Africa sometimes follow the national style using a Nguni shield.[13] Women traditionally display their coats of arms on a diamond-shaped lozenge; abbesses follow this tradition or use the cartouche.

Personal design

In the Roman Catholic Church, unless a new bishop has a family coat of arms, he typically adopts within his shield symbols that indicate his interests or past service. Devotion to a particular saint is represented by symbols established in iconography and heraldic tradition. In the Church of England, new bishops typically choose a coat that looks entirely non-clerical, not least because their descendants may seek reassignment of the arms, and few of them are likely to be clerics.

The first rule of heraldry is the rule of tincture: "Colour must not appear upon colour, nor metal upon metal."[14] The heraldic metals are gold and silver, usually represented as yellow and white, while red, green, blue, purple and black normally comprise the colors. Heraldic bearings are intended for recognition at a distance (in battle), and a contrast of light metal against dark color is desirable. The same principle can be seen in the choice of colors for most license plates.

This rule of tincture is often broken in clerical arms: the flag and arms of Vatican City notably have yellow (gold) and white (silver) placed together. In Byzantine tradition, colors have a mystical interpretation. Because gold and silver express sublimity and solemnity, combinations of the two are often used regardless of the rule of tincture.[15]

Marshalling

Arms of an Anglican bishop marshalled with those of the diocese (left shield) and spouse (right shield)

If a bishop is a diocesan bishop, it is customary for him to combine his arms with the arms of the diocese following normal heraldic rules.[3] This combining is termed marshalling, and is normally accomplished by impalement, placing the arms of the diocese to the viewer's left (dexter in heraldry) and the personal arms to the viewer's right. The arms of Thomas Arundel are found impaled with those of the See of Canterbury in a document from 1411.[16] In Germany and Switzerland, quartering is the norm rather than impalement. Guy Selvester, an American ecclesiastical heraldist, says if arms are not designed with care, marshalling can lead to "busy", crowded shields. Crowding can be reduced by placing a smaller shield overlapping the larger shield, known as an inescutcheon or an escutcheon surtout. In the arms of Heinrich Mussinghoff, Bishop of Aachen, the personal arms are placed in front of the diocesan arms, but the opposite arrangement is found in front on the arms of Paul Gregory Bootkoski, Bishop of Metuchen.[17][18] Cardinals sometimes combine their personal arms with the arms of the Pope who named them a cardinal. As Prefect of the Pontifical Household, Jacques Martin impaled his personal arms with those of three successive pontiffs.[19] A married Church of England bishop combines his arms with those of his wife and the diocese on two separate shields placed accollé, or side-by-side.[20]

Roman Catholic bishops in England historically used only their personal arms, as dioceses established by the See of Rome are not part of the official state Church of England and cannot be recognized in law,[21][10] though in Scotland the legal situation has been different and many Roman Catholic dioceses have arms. If a suffragan or auxiliary bishop has a personal coat of arms, he does not combine it with the arms of the diocese he serves.[2]

Around the shield

Arms of eighteenth-century Archbishop Arthur-Richard Dillon with a green galero (hat) and Patriarchal cross above the shield, and the Order of the Holy Spirit below, and showing fifteen tassels before ten became standard

The shield is the core of heraldry, but other elements are placed above, below, and around the shield, and are usually collectively called external ornaments.[2] The entire composition is called the achievement of arms or the armorial bearings. Some of these accessories are unique to Church armory or differ notably from those which normally accompany a shield.

Ecclesiastical hat

The ecclesiastical hat is a distinctive part of the achievement of arms of a Roman Catholic cleric. This hat, called a galero (or gallero), was originally a pilgrim's hat like a sombrero. It was granted in red to cardinals by Pope Innocent IV at the First Council of Lyon in the 13th century, and was adopted by heraldry almost immediately. The galero in various colors and forms was used in heraldic achievements starting with its adoption in the arms of bishops in the 16th century. In the 19th century the galero was viewed heraldically as specifically "Catholic",[22] but the Public Register of Arms in Scotland show Roman Catholic, presbyterian Church of Scotland and Anglican Episcopalian clergy all using the wide brimmed, low crowned hat. The galero is ornamented with tassels (also called houppes or fiocchi) indicating the cleric's current place in the hierarchy; the number became significant beginning in the 16th century, and the meaning was fixed, for Catholic clergy, in 1832.[23] A bishop's galero is green with six tassels on each side; the color originated in Spain where formerly a green hat was actually worn by bishops.[24] A territorial abbot was equivalent to a bishop and used a green galero. An archbishop's galero is green but has ten tassels. Bishops in Switzerland formerly used ten tassels like an archbishop because they were under the immediate jurisdiction of the Holy See and not part of an archiepiscopal province.[25] Both patriarchs and cardinals have hats with fifteen tassels. A cardinal's hat is red or scarlet while a patriarch who is not also a cardinal uses a green hat; the patriarch's tassels are interwoven with gold.[2] Primates may use the same external ornaments as patriarchs.[26][27]

The depiction of the galero in arms can vary greatly depending on the artist's style. The top of the hat may be shown flat or round. Sometimes the brim is shown much narrower; with a domed top it can look like a cappello romano with tassels, but in heraldry it is still called a galero. The tassels may be represented as knotted cords.

Arms of Bishop Joseph Zen of Hong Kong with the simple Latin cross, and a violet galero (prior to his elevation to cardinal priest)

An exception is made for Chinese bishops, who often avoid using green hat in their arms since "wearing a green hat" is the Chinese idiom for cuckold.[28] Rather than green, these bishops use a variety of colors from violet and black to blue, or scarlet if a cardinal. A cross behind the shield denotes a bishop.

Lesser Roman Catholic prelates use a variety of colors. Violet hats were once actually worn by certain monsignors,[29] and so in heraldry they have used a violet hat with red or violet tassels in varying numbers, currently fixed at six on each side. The lowest grade of monsignor, a Chaplain of His Holiness, uses a black hat with violet tassels.[30] The superior general of an order displays a black galero with six tassels on each side, while provincial superiors and abbots use a black galero with six or three tassels on each side, although Norbertines (White Canons) use a white galero. Although a priest would rarely assume arms unless he had an ancestral right to arms independent of his clerical state, a priest would use a simple black ecclesiastical hat with a single tassel on each side. Priests who hold an office such as rector would have two tassels on each side.[31]

Clergy of the Church of England who were not bishops historically bore arms identical to a layman, with a shield, helm and crest, and no ecclesiastical hat. In England in 1976 a system for deans, archdeacons and canons was authorized by the College of Arms, allowing a black ecclesiastical hat, black or violet cords, and three violet or red tassels on each side.[32][33][9] A priest uses a black and white cord with a single tassel on each side, and a deacon a hat without tassels. A Doctor of Divinity may have cords interwoven with red and a hat appropriate to the degree, and members of the Ecclesiastical Household add a Tudor rose on the front of the hat. According to Boutell's Heraldry, this system represents the practice of the Church in England in the 16th century.[34]

Within Presbyterian Church heraldry, a minister's hat is represented as black with a single tassel on each side, sometimes blue, though a doctoral bonnet or Geneva cap may replace the brimmed hat.[35] Clergy of the Chapel Royal display red tassels. The office of moderator does not have corporate arms,[36] but for official occasions, a moderator may add tassels to his personal arms to indicate parity with offices of other churches: three for a moderator of a presbytery, and six for a moderator of a regional synod.[37] The moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland now uses a differenced version of the General Assembly's arms, with a hat having a blue cord and ten tassels on each side, and may also show the moderator's staff, a gold Celtic crosier, behind the shield as can be seen in vol 41, p 152 of the Scots Public Register.

Cross

Coat of arms of the Bishop Antônio de Castro Mayer, carved in a wooden door in a Church.

In the Catholic Church, display of a cross behind the shield is restricted to bishops as a mark of their dignity.[38] The cross of an ordinary bishop has a single horizontal bar or traverse, also known as a Latin cross. A patriarch uses the patriarchal cross with two traverses, also called the cross of Lorraine. The papal cross has three traverses, but this is never displayed behind the papal arms.

Beginning in the 15th century, the cross with a double traverse is seen on the arms of archbishops, and relates to their processional cross and the jurisdiction it symbolizes.[39][40] Except for cardinals of the Roman Curia, most cardinals head an archdiocese and use an archiepiscopal cross on their arms. Other cardinals use a simple Latin cross,[41] as is found in the arms of Cardinal Joseph Zen, bishop emeritus of Hong Kong, because Hong Kong is not an archdiocese.

Today all cardinals are required to be bishops, but priests named cardinal at an advanced age often petition the Pope for an exception to this rule. Bruno Heim says that since the cross is one heraldic emblem that only bishops have the right to bear, cardinals who are not bishops do not use it.[42][43] Notable examples are Cardinals Albert Vanhoye and Avery Dulles; the latter's arms do display a cross.[44]

Mitre and pallium

Emblem of Syriac Orthodox Church: and Eastern crozier crossed with a blessing cross beneath a Syriac bishop's turban

Coat of arms of Francis de Sales, bishop of Geneva displayed on an oval shield with both mitre and galero above, and motto below

What a Bishop's Coat of Arms would have looked like before the rules were changed in 1969. This is not an official version.

In the western churches, the mitre was placed above the shield of all persons who were entitled to wear the mitre, including abbots. It substituted for the helmet of military arms, but also appeared as a crest placed atop a helmet, as was common in German heraldry.[2] In the Anglican Churches, the mitre is still placed above the arms of bishops and not an ecclesiastical hat. In the Roman Catholic Church, the use of the mitre above the shield on the personal arms of clergy was suppressed in 1969,[45] and is now found only on some corporate arms, like those of dioceses. Previously, the mitre was often included under the hat,[46] and even in the arms of a cardinal, the mitre was not entirely displaced.[47]

The mitre may be shown in all sorts of colours. It may be represented either gold or jewelled, the former more common in English heraldry.[48] A form of mitre with coronet is proper to the Bishop of Durham because of his role as Prince-Bishop of the palatinate of Durham.[49] For similar reasons the Bishop of Durham and some other bishops display a sword behind the shield, pointed downward to signify a former civil jurisdiction.[50][51]

The pallium is a distinctive vestment of metropolitan archbishops, and may be found in their bearings as well as the corporate arms of archdioceses, displayed either above or below the shield. The pallium is sometimes seen within the shield itself. With the exception of York, the archiepiscopal dioceses in England and Ireland include the pallium within the shield.[52]

Crosier

Franz Christoph von Hutten's coat of arms from the 18th century with mitre, staff, and sword

The crosier was displayed as a symbol of pastoral jurisdiction by bishops, abbots, abbesses, and cardinals even if they were not bishops. The crosier of a bishop is turned outward or to the right. Frequently the crosier of an abbot or abbess is turned inward, either toward the mitre or to the left, but this distinction is disputed and is not an absolute rule.[53][54] Pope Alexander VII decreed in 1659 that the crosiers of abbots include a sudarium or veil, but this is not customary in English heraldry.[55] The veil may have arisen because abbots, unlike bishops, did not wear gloves when carrying an actual crosier.[56] Because the cross has similar symbolism,[34] the crosier was suppressed for cardinals and bishops by the Catholic Church in 1969, and is now used only on some corporate arms, and the personal arms of abbots and some abbesses.[57] In English custom and in the Anglican Churches, two crosiers are often found crossed in saltire behind the shield.[58][48] In the Lutheran Church of Sweden, the crosier is displayed in the arms of bishops in office but is removed when a bishop retires.

A rendition of the coat of arms of the Diocese of Cubao, showing the mitre, crozier, and cross.

A bourdon or knobbed staff is shown behind the arms of some priors and prioresses as a symbol of office analogous to the crosier.[59][60] Arms of priors from the 15th century had a banner surrounding the shield,[61] but today this is often a rosary.[62]

Mantle

Arms of Cardinal Josyf Slipyj, major archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, with mantling

Mantling was originally a piece of material attached to a helmet and covering the shoulders, possibly to protect from the sun. In secular heraldry the mantling was depicted shredded, as if from battle. In the 17th and 18th centuries, another form of mantling called a "robe of estate" became prominent.[63] This form is used especially in the Orthodox Churches, where bishops display a mantle tied with cords and tassels above the shield. The heraldic mantle is similar to the mantiya, and represents the bishop's authority. It can also be found in the arms of the Grand Master of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.[64]

The outside of the mantle may be any color, typically red, while the inside is white or sometimes yellow to distinguish it from a secular mantle.[65] David Johnson suggested that the mantle of all bishops should be white inside, excepting only patriarchs who use ermine, to indicate that all bishops are equally bishops.[66] Above the mantle is a mitre (of the Eastern style) between a processional cross and a crosier. The earliest examples of the arms of Orthodox hierarchs have the cross to the dexter of the mitre and the bishop's staff to sinister, but opposite examples exist. An abbot (archimandrite or hegumen) should display a veiled abbot's staff to distinguish it from the bishop's staff.

Coat of arms of an Eastern Catholic prelate, combining elements of both Eastern and Western ecclesiastical heraldry

Archpriests and priests would use a less ornate mantle in their arms, and an ecclesiastical hat of the style they wear liturgically. Although an Orthodox monk (not an abbot) displaying personal arms is rare, a hieromonk (monk who has been ordained a priest) would appropriately display a monastic hat (klobuk) and a black cloak or veil suggestive of his attire, and a hierodeacon (monastic deacon) would display an orarion behind the shield.

A shield in front of a mantle or cloak may be found among bishops of the Eastern Catholic Churches.[67] However, some Eastern ecclesiastical variations omit the mantle but retain the mitre, cross and staff.[68] Maronite bishops traditionally display a pastoral staff behind the shield, topped with a globe and cross or a cross within a globe.[69] Eastern Catholic bishops may follow the Roman style with a low crowned, wide brimmed ecclesiastical hat, although the shield itself is often rendered in a Byzantine artistic style, and a mitre if present would be in the appropriate liturgical style.[70]

Motto

A motto is a short phrase usually appearing below the shield as a statement of belief. Catholic bishops and Presbyterian churches use a motto in their arms,[71] though it is rare among Anglican bishops.[48][2] A notable exception is the motto on the coat of arms of Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury.

Gustavo Testa, created cardinal in December 1959, quickly selected as his arms a shield with the words sola gratia tua and the motto et patria et cor in order to meet a publishing deadline. Literally these phrases mean "only by your favor" and "both fatherland and heart". Testa explained to Pope John XXIII that the shield meant "I am a cardinal because of you alone", and the motto meant "because I am from Bergamo and a friend".[72]

Papal insignia

Main article: Papal regalia and insignia

Pope Leo XI's coat of arms, the family arms of the Medici

Saint Peter was represented holding keys as early as the fifth century. As the Roman Catholic Church considers him the first pope and bishop of Rome, the keys were adopted as a papal emblem; they first appear with papal arms in the 13th century.[73] Two keys perpendicular were often used on coins, but beginning in the 15th century were used to represent St. Peter's Basilica. Perpendicular keys last appeared in the shield of the papacy in 1555, after which the crossed keys are used exclusively.[74] The keys are gold and silver, with the gold key placed to dexter (viewer's left) on the personal arms of the Pope, although two silver keys or two gold keys were used late into the 16th century.[75] The keys as a symbol of Saint Peter may be found within many coats of arms; the coat of arms of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen displayed two argent (silver) crossed keys as Saint Peter is the patron saint of the Bremian archiepiscopal cathedral.

The Papal Tiara or triregnum is the three-tiered crown used by the Pope as a sovereign power. It is first found as an independent emblem in the 13th century, though at that time with only one coronet.[76] In the 15th century, the tiara was combined with the keys above the papal shield. The tiara and keys together within a shield form the arms of Vatican City. In heraldry, the white tiara is depicted with a bulbous shape and with two attached red strips called lappets or infulae.[77] The coat of arms of Pope Benedict XVI sparked controversy by displaying a mitre and pallium instead of the customary tiara.

Besides the Holy See, another Catholic see has the right to bear the triple tiara in its coat of arms: the Patriarchate of Lisbon.[78] The title of Patriarch of Lisbon was created in 1716 and is held by the archbishop of Lisbon since 1740. While the coat of arms of the Holy See combines the tiara with the crossed keys of St. Peter, that of the Lisbon Patriarchate combines it with a processional cross and a pastoral staff.

Rendition of Pope Pius IX's coat of arms with tiara, keys and supporters

The red and gold striped ombrellino or pavilion was originally a processional canopy or sunshade and can be found so depicted as early as the 12th century.[79] The earliest use of the ombrellino in heraldry is in the 1420s when it was placed above the shield of Pope Martin V. It is more commonly used together with the keys, a combination first found under Pope Alexander VI.[80] This combined badge represents the temporal power of Vatican City between Papal reigns, when the acting head of state is the cardinal Camerlengo. The badge first appeared with a cardinal's personal arms on coins minted by order of the Camerlengo, Cardinal Armellini, during the inter-regnum of 1521. During the 17th and 18th centuries, it appeared on coins minted sede vacante by papal legates, and on coins minted in 1746 and 1771 while a pope reigned.[81] The ombrellino appears in the arms of basilicas since the 16th century, with ornamentation for major basilicas. If found in a family's coat of arms, it indicates that a relative had been pope.[82]

Emblem of Bremen's archbishop (red shield) within the emblem of Hagen i.B.

The papal coats of arms are often depicted with angels as supporters.[83] Other Catholic or Anglican clergy do not use supporters unless they were awarded as a personal honor, or were inherited with family arms.[48][2] Some cathedral arms use a single chair (cathedra) as a supporter.[84]

Chivalric insignia

Roman Catholic clergy may not display insignia of knighthood in their arms, except awards received in the Order of the Holy Sepulchre or the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. If entitled, Roman Catholic clergy may display the red Jerusalem Cross for the former or the Maltese cross for the latter behind the shield, or may display the ribbon of their rank in the order.[85] This restriction does not apply to laymen who have been knighted in any royal or Papal order, who may display the insignia of their rank, either a ribbon at the base of the shield or a chain surrounding the shield.

Church of England clergy may display chivalric insignia. The Dean of Westminster is also the Dean of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, and displays the civil badge of that order.[86]

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Coat of arms of Cardinal Agostino Bausa in the courtyard of the archiepiscopal palace of Florence

Ecclesiastical heraldry refers to the use of heraldry within the Christian Church for dioceses and Christian clergy. Initially used to mark documents, ecclesiastical heraldry evolved as a system for identifying people and dioceses. It is most formalized within the Catholic Church, where most bishops, including the Pope, have a personal coat of arms. Clergy in Anglican, Lutheran, Eastern Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches follow similar customs, as do institutions such as schools and dioceses.

Ecclesiastical heraldry differs notably from other heraldry in the use of special insignia around the shield to indicate rank in a church or denomination. The most prominent of these insignia is the low crowned, wide brimmed ecclesiastical hat, commonly the Roman galero. The color and ornamentation of this hat indicate rank. Cardinals are famous for the "red hat", but other offices and other churches have distinctive hat colors, such as black for ordinary clergy and green for bishops, customarily with a number of tassels increasing with rank.

Other insignia include the processional cross, the mitre and the crosier. Eastern traditions favor the use of their own style of head gear and crosier, and the use of the mantle or cloak rather than the ecclesiastical hat. The motto and certain shapes of shields are more common in ecclesiastical heraldry, while supporters and crests are less common. The papal coats of arms have their own heraldic customs, primarily the Papal Tiara (or mitre), the keys of Saint Peter, and the ombrellino (umbrella). Pope Benedict XVI replaced the use of the Papal Tiara in his coat of arms with a mitre. He was the first pope to do so, despite the fact that Pope Paul VI was the last pope to be crowned with the tiara. The arms of institutions have slightly different traditions, using the mitre and crozier more often than is found in personal arms, though there is a wide variation in uses by different churches. The arms used by organizations are called impersonal or corporate arms.

Contents

1 History

2 Shield

2.1 Personal design

2.2 Marshalling

3 Around the shield

3.1 Ecclesiastical hat

3.2 Cross

3.3 Mitre and pallium

3.4 Crosier

3.5 Mantle

3.6 Motto

4 Papal insignia

5 Chivalric insignia

6 References

7 Bibliography

8 External links

History

12th-century seal of Stefan of Uppsala

Reproduction of a medieval Knights Templar Seal

personal seal of Martin Luther from 1530, now a symbol of Lutheranism

Heraldry developed in medieval Europe from the late 11th century, originally as a system of personal badges of the warrior classes, which served, among other purposes, as identification on the battlefield. The same insignia were used on seals to identify documents. The earliest seals bore a likeness of the owner of the seal, with the shield and heraldic insignia included.[1] Over time, the seals were reduced to just the shield.

The Church likewise identified the origin and ownership of documents and buildings with seals, which were typically a pointed oval called a vesica to distinguish from round seals in non-religious use.[2] Edward I of England decreed in 1307 that all legal documents required a seal.[3] These seals initially depicted a person, but as secular seals began to depict only a shield, clergy likewise used seals with heraldic insignia.[4] Personal seals of bishops and abbots continued to be used after their deaths, gradually becoming an impersonal seal.[3] Clergy tended to replace military devices with clerical devices. The shield was retained, but ecclesiastical hats often replaced helmets and coronets. In some religious arms a skull replaces the helmet.[5]

The structure of Church heraldry developed significantly in the 17th century when a system for ecclesiastical hats attributed to Pierre Palliot came into use.[6] The full system of emblems around the shield was regulated in the Catholic Church by the letter of Pope Pius X Inter multiplices curas of February 21, 1905, while the composition of the shield itself was regulated through the Heraldry Commission of the Roman Curia until this office was abolished by Pope John XXIII in 1960.[7] The Annuario Pontificio ceased publishing the arms of Cardinals and previous Popes after 1969. International custom and national law govern limited aspects of Church heraldry, but shield composition is now largely guided by expert advice. Archbishop Bruno Heim, a noted ecclesiastical armorist (designer of arms), said

Ecclesiastical heraldry is not determined by heraldic considerations alone, but also by doctrinal, liturgical and canonical factors. It not only produces arms denoting members of the ecclesiastical state but shows the rank of the bearer.... In the eyes of the Church it is sufficient to determine who has a right to bear an ecclesiastical coat of arms and under what conditions the different insignia are acquired or lost... The design of prelatial arms is often a disastrous defiance of the rules of heraldry, if only as a breach of good taste.[8]

A similar system for the Church of England was approved in 1976.[9] The traditions of Eastern Christian heraldry have less developed regulation. Eastern secular coats of arms often display a shield before a mantle topped with a crown. Eastern clergy often display coats of arms according to this style, replacing the crown with an appropriate hat drawn from liturgical use.

Marking documents is the most common use of arms in the Church today. A Roman Catholic bishop's coat of arms was formerly painted on miniature wine barrels and presented during the ordination ceremony.[10][11] Cardinals may place their coat of arms outside the church of their title in Rome.[12] Impersonal arms are often used as the banner of a school or religious community.

Shield

Arms of an abbess displayed on a lozenge with crosier turned left

The shield is the normal device for displaying a coat of arms. Clergy have used less-military shapes such as the oval cartouche, but the shield has always been a clerical option. Clergy in Italy often use a shield shaped like a horse's face-armor. Clergy in South Africa sometimes follow the national style using a Nguni shield.[13] Women traditionally display their coats of arms on a diamond-shaped lozenge; abbesses follow this tradition or use the cartouche.

Personal design

In the Roman Catholic Church, unless a new bishop has a family coat of arms, he typically adopts within his shield symbols that indicate his interests or past service. Devotion to a particular saint is represented by symbols established in iconography and heraldic tradition. In the Church of England, new bishops typically choose a coat that looks entirely non-clerical, not least because their descendants may seek reassignment of the arms, and few of them are likely to be clerics.

The first rule of heraldry is the rule of tincture: "Colour must not appear upon colour, nor metal upon metal."[14] The heraldic metals are gold and silver, usually represented as yellow and white, while red, green, blue, purple and black normally comprise the colors. Heraldic bearings are intended for recognition at a distance (in battle), and a contrast of light metal against dark color is desirable. The same principle can be seen in the choice of colors for most license plates.

This rule of tincture is often broken in clerical arms: the flag and arms of Vatican City notably have yellow (gold) and white (silver) placed together. In Byzantine tradition, colors have a mystical interpretation. Because gold and silver express sublimity and solemnity, combinations of the two are often used regardless of the rule of tincture.[15]

Marshalling

Arms of an Anglican bishop marshalled with those of the diocese (left shield) and spouse (right shield)

If a bishop is a diocesan bishop, it is customary for him to combine his arms with the arms of the diocese following normal heraldic rules.[3] This combining is termed marshalling, and is normally accomplished by impalement, placing the arms of the diocese to the viewer's left (dexter in heraldry) and the personal arms to the viewer's right. The arms of Thomas Arundel are found impaled with those of the See of Canterbury in a document from 1411.[16] In Germany and Switzerland, quartering is the norm rather than impalement. Guy Selvester, an American ecclesiastical heraldist, says if arms are not designed with care, marshalling can lead to "busy", crowded shields. Crowding can be reduced by placing a smaller shield overlapping the larger shield, known as an inescutcheon or an escutcheon surtout. In the arms of Heinrich Mussinghoff, Bishop of Aachen, the personal arms are placed in front of the diocesan arms, but the opposite arrangement is found in front on the arms of Paul Gregory Bootkoski, Bishop of Metuchen.[17][18] Cardinals sometimes combine their personal arms with the arms of the Pope who named them a cardinal. As Prefect of the Pontifical Household, Jacques Martin impaled his personal arms with those of three successive pontiffs.[19] A married Church of England bishop combines his arms with those of his wife and the diocese on two separate shields placed accollé, or side-by-side.[20]

Roman Catholic bishops in England historically used only their personal arms, as dioceses established by the See of Rome are not part of the official state Church of England and cannot be recognized in law,[21][10] though in Scotland the legal situation has been different and many Roman Catholic dioceses have arms. If a suffragan or auxiliary bishop has a personal coat of arms, he does not combine it with the arms of the diocese he serves.[2]

Around the shield

Arms of eighteenth-century Archbishop Arthur-Richard Dillon with a green galero (hat) and Patriarchal cross above the shield, and the Order of the Holy Spirit below, and showing fifteen tassels before ten became standard

The shield is the core of heraldry, but other elements are placed above, below, and around the shield, and are usually collectively called external ornaments.[2] The entire composition is called the achievement of arms or the armorial bearings. Some of these accessories are unique to Church armory or differ notably from those which normally accompany a shield.

Ecclesiastical hat

The ecclesiastical hat is a distinctive part of the achievement of arms of a Roman Catholic cleric. This hat, called a galero (or gallero), was originally a pilgrim's hat like a sombrero. It was granted in red to cardinals by Pope Innocent IV at the First Council of Lyon in the 13th century, and was adopted by heraldry almost immediately. The galero in various colors and forms was used in heraldic achievements starting with its adoption in the arms of bishops in the 16th century. In the 19th century the galero was viewed heraldically as specifically "Catholic",[22] but the Public Register of Arms in Scotland show Roman Catholic, presbyterian Church of Scotland and Anglican Episcopalian clergy all using the wide brimmed, low crowned hat. The galero is ornamented with tassels (also called houppes or fiocchi) indicating the cleric's current place in the hierarchy; the number became significant beginning in the 16th century, and the meaning was fixed, for Catholic clergy, in 1832.[23] A bishop's galero is green with six tassels on each side; the color originated in Spain where formerly a green hat was actually worn by bishops.[24] A territorial abbot was equivalent to a bishop and used a green galero. An archbishop's galero is green but has ten tassels. Bishops in Switzerland formerly used ten tassels like an archbishop because they were under the immediate jurisdiction of the Holy See and not part of an archiepiscopal province.[25] Both patriarchs and cardinals have hats with fifteen tassels. A cardinal's hat is red or scarlet while a patriarch who is not also a cardinal uses a green hat; the patriarch's tassels are interwoven with gold.[2] Primates may use the same external ornaments as patriarchs.[26][27]

The depiction of the galero in arms can vary greatly depending on the artist's style. The top of the hat may be shown flat or round. Sometimes the brim is shown much narrower; with a domed top it can look like a cappello romano with tassels, but in heraldry it is still called a galero. The tassels may be represented as knotted cords.

Arms of Bishop Joseph Zen of Hong Kong with the simple Latin cross, and a violet galero (prior to his elevation to cardinal priest)

An exception is made for Chinese bishops, who often avoid using green hat in their arms since "wearing a green hat" is the Chinese idiom for cuckold.[28] Rather than green, these bishops use a variety of colors from violet and black to blue, or scarlet if a cardinal. A cross behind the shield denotes a bishop.

Lesser Roman Catholic prelates use a variety of colors. Violet hats were once actually worn by certain monsignors,[29] and so in heraldry they have used a violet hat with red or violet tassels in varying numbers, currently fixed at six on each side. The lowest grade of monsignor, a Chaplain of His Holiness, uses a black hat with violet tassels.[30] The superior general of an order displays a black galero with six tassels on each side, while provincial superiors and abbots use a black galero with six or three tassels on each side, although Norbertines (White Canons) use a white galero. Although a priest would rarely assume arms unless he had an ancestral right to arms independent of his clerical state, a priest would use a simple black ecclesiastical hat with a single tassel on each side. Priests who hold an office such as rector would have two tassels on each side.[31]

Clergy of the Church of England who were not bishops historically bore arms identical to a layman, with a shield, helm and crest, and no ecclesiastical hat. In England in 1976 a system for deans, archdeacons and canons was authorized by the College of Arms, allowing a black ecclesiastical hat, black or violet cords, and three violet or red tassels on each side.[32][33][9] A priest uses a black and white cord with a single tassel on each side, and a deacon a hat without tassels. A Doctor of Divinity may have cords interwoven with red and a hat appropriate to the degree, and members of the Ecclesiastical Household add a Tudor rose on the front of the hat. According to Boutell's Heraldry, this system represents the practice of the Church in England in the 16th century.[34]

Within Presbyterian Church heraldry, a minister's hat is represented as black with a single tassel on each side, sometimes blue, though a doctoral bonnet or Geneva cap may replace the brimmed hat.[35] Clergy of the Chapel Royal display red tassels. The office of moderator does not have corporate arms,[36] but for official occasions, a moderator may add tassels to his personal arms to indicate parity with offices of other churches: three for a moderator of a presbytery, and six for a moderator of a regional synod.[37] The moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland now uses a differenced version of the General Assembly's arms, with a hat having a blue cord and ten tassels on each side, and may also show the moderator's staff, a gold Celtic crosier, behind the shield as can be seen in vol 41, p 152 of the Scots Public Register.

Cross

Coat of arms of the Bishop Antônio de Castro Mayer, carved in a wooden door in a Church.

In the Catholic Church, display of a cross behind the shield is restricted to bishops as a mark of their dignity.[38] The cross of an ordinary bishop has a single horizontal bar or traverse, also known as a Latin cross. A patriarch uses the patriarchal cross with two traverses, also called the cross of Lorraine. The papal cross has three traverses, but this is never displayed behind the papal arms.

Beginning in the 15th century, the cross with a double traverse is seen on the arms of archbishops, and relates to their processional cross and the jurisdiction it symbolizes.[39][40] Except for cardinals of the Roman Curia, most cardinals head an archdiocese and use an archiepiscopal cross on their arms. Other cardinals use a simple Latin cross,[41] as is found in the arms of Cardinal Joseph Zen, bishop emeritus of Hong Kong, because Hong Kong is not an archdiocese.

Today all cardinals are required to be bishops, but priests named cardinal at an advanced age often petition the Pope for an exception to this rule. Bruno Heim says that since the cross is one heraldic emblem that only bishops have the right to bear, cardinals who are not bishops do not use it.[42][43] Notable examples are Cardinals Albert Vanhoye and Avery Dulles; the latter's arms do display a cross.[44]

Mitre and pallium

Emblem of Syriac Orthodox Church: and Eastern crozier crossed with a blessing cross beneath a Syriac bishop's turban

Coat of arms of Francis de Sales, bishop of Geneva displayed on an oval shield with both mitre and galero above, and motto below

What a Bishop's Coat of Arms would have looked like before the rules were changed in 1969. This is not an official version.

In the western churches, the mitre was placed above the shield of all persons who were entitled to wear the mitre, including abbots. It substituted for the helmet of military arms, but also appeared as a crest placed atop a helmet, as was common in German heraldry.[2] In the Anglican Churches, the mitre is still placed above the arms of bishops and not an ecclesiastical hat. In the Roman Catholic Church, the use of the mitre above the shield on the personal arms of clergy was suppressed in 1969,[45] and is now found only on some corporate arms, like those of dioceses. Previously, the mitre was often included under the hat,[46] and even in the arms of a cardinal, the mitre was not entirely displaced.[47]

The mitre may be shown in all sorts of colours. It may be represented either gold or jewelled, the former more common in English heraldry.[48] A form of mitre with coronet is proper to the Bishop of Durham because of his role as Prince-Bishop of the palatinate of Durham.[49] For similar reasons the Bishop of Durham and some other bishops display a sword behind the shield, pointed downward to signify a former civil jurisdiction.[50][51]

The pallium is a distinctive vestment of metropolitan archbishops, and may be found in their bearings as well as the corporate arms of archdioceses, displayed either above or below the shield. The pallium is sometimes seen within the shield itself. With the exception of York, the archiepiscopal dioceses in England and Ireland include the pallium within the shield.[52]

Crosier

Franz Christoph von Hutten's coat of arms from the 18th century with mitre, staff, and sword

The crosier was displayed as a symbol of pastoral jurisdiction by bishops, abbots, abbesses, and cardinals even if they were not bishops. The crosier of a bishop is turned outward or to the right. Frequently the crosier of an abbot or abbess is turned inward, either toward the mitre or to the left, but this distinction is disputed and is not an absolute rule.[53][54] Pope Alexander VII decreed in 1659 that the crosiers of abbots include a sudarium or veil, but this is not customary in English heraldry.[55] The veil may have arisen because abbots, unlike bishops, did not wear gloves when carrying an actual crosier.[56] Because the cross has similar symbolism,[34] the crosier was suppressed for cardinals and bishops by the Catholic Church in 1969, and is now used only on some corporate arms, and the personal arms of abbots and some abbesses.[57] In English custom and in the Anglican Churches, two crosiers are often found crossed in saltire behind the shield.[58][48] In the Lutheran Church of Sweden, the crosier is displayed in the arms of bishops in office but is removed when a bishop retires.

A rendition of the coat of arms of the Diocese of Cubao, showing the mitre, crozier, and cross.

A bourdon or knobbed staff is shown behind the arms of some priors and prioresses as a symbol of office analogous to the crosier.[59][60] Arms of priors from the 15th century had a banner surrounding the shield,[61] but today this is often a rosary.[62]

Mantle

Arms of Cardinal Josyf Slipyj, major archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, with mantling

Mantling was originally a piece of material attached to a helmet and covering the shoulders, possibly to protect from the sun. In secular heraldry the mantling was depicted shredded, as if from battle. In the 17th and 18th centuries, another form of mantling called a "robe of estate" became prominent.[63] This form is used especially in the Orthodox Churches, where bishops display a mantle tied with cords and tassels above the shield. The heraldic mantle is similar to the mantiya, and represents the bishop's authority. It can also be found in the arms of the Grand Master of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.[64]

The outside of the mantle may be any color, typically red, while the inside is white or sometimes yellow to distinguish it from a secular mantle.[65] David Johnson suggested that the mantle of all bishops should be white inside, excepting only patriarchs who use ermine, to indicate that all bishops are equally bishops.[66] Above the mantle is a mitre (of the Eastern style) between a processional cross and a crosier. The earliest examples of the arms of Orthodox hierarchs have the cross to the dexter of the mitre and the bishop's staff to sinister, but opposite examples exist. An abbot (archimandrite or hegumen) should display a veiled abbot's staff to distinguish it from the bishop's staff.

Coat of arms of an Eastern Catholic prelate, combining elements of both Eastern and Western ecclesiastical heraldry

Archpriests and priests would use a less ornate mantle in their arms, and an ecclesiastical hat of the style they wear liturgically. Although an Orthodox monk (not an abbot) displaying personal arms is rare, a hieromonk (monk who has been ordained a priest) would appropriately display a monastic hat (klobuk) and a black cloak or veil suggestive of his attire, and a hierodeacon (monastic deacon) would display an orarion behind the shield.

A shield in front of a mantle or cloak may be found among bishops of the Eastern Catholic Churches.[67] However, some Eastern ecclesiastical variations omit the mantle but retain the mitre, cross and staff.[68] Maronite bishops traditionally display a pastoral staff behind the shield, topped with a globe and cross or a cross within a globe.[69] Eastern Catholic bishops may follow the Roman style with a low crowned, wide brimmed ecclesiastical hat, although the shield itself is often rendered in a Byzantine artistic style, and a mitre if present would be in the appropriate liturgical style.[70]

Motto

A motto is a short phrase usually appearing below the shield as a statement of belief. Catholic bishops and Presbyterian churches use a motto in their arms,[71] though it is rare among Anglican bishops.[48][2] A notable exception is the motto on the coat of arms of Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury.

Gustavo Testa, created cardinal in December 1959, quickly selected as his arms a shield with the words sola gratia tua and the motto et patria et cor in order to meet a publishing deadline. Literally these phrases mean "only by your favor" and "both fatherland and heart". Testa explained to Pope John XXIII that the shield meant "I am a cardinal because of you alone", and the motto meant "because I am from Bergamo and a friend".[72]

Papal insignia

Main article: Papal regalia and insignia

Pope Leo XI's coat of arms, the family arms of the Medici

Saint Peter was represented holding keys as early as the fifth century. As the Roman Catholic Church considers him the first pope and bishop of Rome, the keys were adopted as a papal emblem; they first appear with papal arms in the 13th century.[73] Two keys perpendicular were often used on coins, but beginning in the 15th century were used to represent St. Peter's Basilica. Perpendicular keys last appeared in the shield of the papacy in 1555, after which the crossed keys are used exclusively.[74] The keys are gold and silver, with the gold key placed to dexter (viewer's left) on the personal arms of the Pope, although two silver keys or two gold keys were used late into the 16th century.[75] The keys as a symbol of Saint Peter may be found within many coats of arms; the coat of arms of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen displayed two argent (silver) crossed keys as Saint Peter is the patron saint of the Bremian archiepiscopal cathedral.

The Papal Tiara or triregnum is the three-tiered crown used by the Pope as a sovereign power. It is first found as an independent emblem in the 13th century, though at that time with only one coronet.[76] In the 15th century, the tiara was combined with the keys above the papal shield. The tiara and keys together within a shield form the arms of Vatican City. In heraldry, the white tiara is depicted with a bulbous shape and with two attached red strips called lappets or infulae.[77] The coat of arms of Pope Benedict XVI sparked controversy by displaying a mitre and pallium instead of the customary tiara.

Besides the Holy See, another Catholic see has the right to bear the triple tiara in its coat of arms: the Patriarchate of Lisbon.[78] The title of Patriarch of Lisbon was created in 1716 and is held by the archbishop of Lisbon since 1740. While the coat of arms of the Holy See combines the tiara with the crossed keys of St. Peter, that of the Lisbon Patriarchate combines it with a processional cross and a pastoral staff.

Rendition of Pope Pius IX's coat of arms with tiara, keys and supporters

The red and gold striped ombrellino or pavilion was originally a processional canopy or sunshade and can be found so depicted as early as the 12th century.[79] The earliest use of the ombrellino in heraldry is in the 1420s when it was placed above the shield of Pope Martin V. It is more commonly used together with the keys, a combination first found under Pope Alexander VI.[80] This combined badge represents the temporal power of Vatican City between Papal reigns, when the acting head of state is the cardinal Camerlengo. The badge first appeared with a cardinal's personal arms on coins minted by order of the Camerlengo, Cardinal Armellini, during the inter-regnum of 1521. During the 17th and 18th centuries, it appeared on coins minted sede vacante by papal legates, and on coins minted in 1746 and 1771 while a pope reigned.[81] The ombrellino appears in the arms of basilicas since the 16th century, with ornamentation for major basilicas. If found in a family's coat of arms, it indicates that a relative had been pope.[82]

Emblem of Bremen's archbishop (red shield) within the emblem of Hagen i.B.

The papal coats of arms are often depicted with angels as supporters.[83] Other Catholic or Anglican clergy do not use supporters unless they were awarded as a personal honor, or were inherited with family arms.[48][2] Some cathedral arms use a single chair (cathedra) as a supporter.[84]

Chivalric insignia

Roman Catholic clergy may not display insignia of knighthood in their arms, except awards received in the Order of the Holy Sepulchre or the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. If entitled, Roman Catholic clergy may display the red Jerusalem Cross for the former or the Maltese cross for the latter behind the shield, or may display the ribbon of their rank in the order.[85] This restriction does not apply to laymen who have been knighted in any royal or Papal order, who may display the insignia of their rank, either a ribbon at the base of the shield or a chain surrounding the shield.

Church of England clergy may display chivalric insignia. The Dean of Westminster is also the Dean of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, and displays the civil badge of that order.[86]

Saturday, 29 April 2017

Thomas Hobbes was a Mongol Pict and related to the North American Indians. This is also true of King John who was also Mongol Pict in ancestry.

Thomas Hobbes was a Mongol Pict and related to the North American Indians. This is also true of King John who was also Mongol Pict in ancestry.

Friday, 28 April 2017

William Windslor is...is he the 2nd because it can't be me. You could just kill a pigeon if...if you need to deny Christ's blood and you need some blood for the remission of sins or you could use the gas lighter efficient version, Ronson version and take Sacraments. Warren C. Lyon was the human sacrifice and he was White which means he had to be the right one worthy of all the glory and the honor. Warren C. Lyon was worthy and an American.